Unknown Target: Uncovering and Detecting Novel In-Flight Attacks to Collision Avoidance (TCAS)

Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2026

Abstract

The Traffic alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) is a mandatory last-resort safeguard against mid-air collisions. Despite its critical safety role, the system’s unauthenticated and unencrypted communication protocols present a long identified security risk. Although researchers have previously demonstrated practical injection attacks, official advisories have assessed these vulnerabilities as confined to laboratory environments, also stating that no mitigation is currently available. In this paper, we challenge both assertions. We present compelling evidence suggesting that an in-flight cyber-attack targeting TCAS has already occurred. Through a detailed analysis of public flight and communications data from a series of anomalous events involving multiple aircraft, we identify a distinct signature consistent with a ghost plane injection attack. We detail how this novel attack exploits legacy protocol features and describe three strategies of increasing sophistication; the most aggressive of these can reduce a target’s perceived range by over 3.5 kilometers, sufficient to trigger collision avoidance advisories on victim aircraft from a significant standoff distance. We implement and experimentally evaluate the attack strategy most consistent with the observed incident, achieving a spoofed range reduction of 1.9 km, confirming its feasibility. Furthermore, to provide a basis for responding to such threats, we propose a novel, backward-compatible methodology to geographically localize the source of such attacks by repurposing the TCAS alert data broadcast by victims. In simulated scenarios of the most plausible attack variant, our approach achieves a median localization accuracy of 855 meters. Applying this technique to real-world incident data, we were able to identify the anomaly and the likely origin of the observed ghost plane injection attack.

Resources

About the publication

Table of contents

Jump to the descriptionThe Washington Mystery

March 1, 2025. Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA).

It was a standard Saturday morning at one of the busiest airports in the United States until chaos erupted on the radio channels.

Multiple pilots approaching the capital began reporting emergency “Resolution Advisories”.

Their instruments were screaming at them to DESCEND to avoid a collision.

But looking out the window? Nothing.

The sky was empty.

Air Traffic Control saw nothing on their radar.

Yet, the aircraft’s safety computers were convinced they were seconds away from impact.

What is TCAS?

The “Traffic alert and Collision Avoidance System” is the last line of defense in the sky.

Air-to-Air

TCAS doesn’t rely on ground control. It’s a conversation directly between planes. Even if the tower goes dark, TCAS keeps planes apart.

Interrogation

Your plane shouts “Who is there?” (Interrogation). Other planes reply “I am here, at this altitude” (Reply).

Distance Measurement

TCAS calculates distance based on Time. It measures how long the radio signal takes to bounce back.

Distance = Time * Speed of Light / 2.

It is mandatory on basically every aircraft in the world1.

The attack: range spoofing

The Washington incident wasn’t a glitch. It was likely a “Range Spoofing” attack exploiting the legacy Mode C protocol. Here is how you create a ghost.

Transponders normally wait 3 microseconds2 before replying to a query. This is a standard rule.

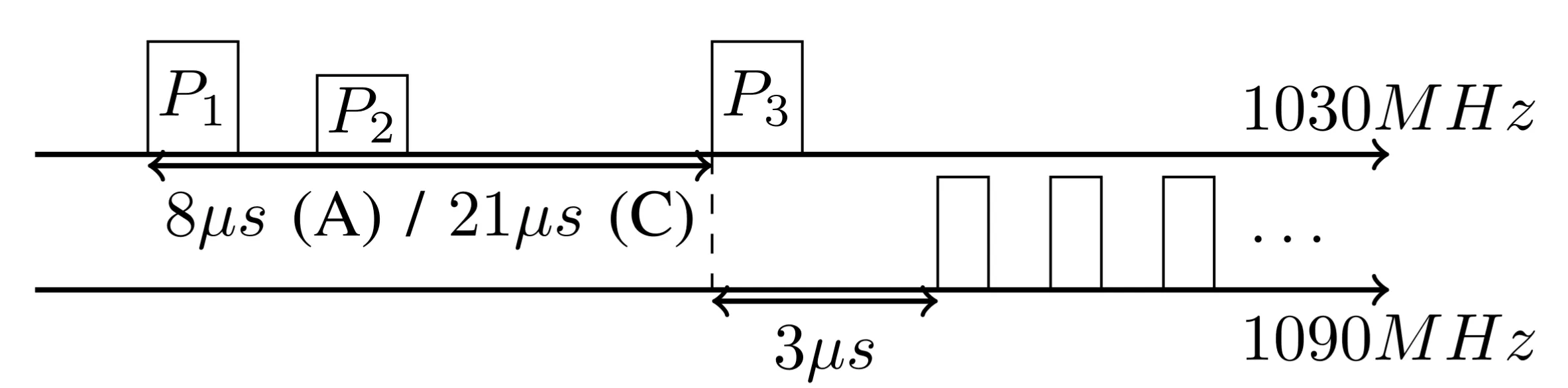

If you see the image above, depicting the Mode C protocol, you can see in the line above the “interrogation” (or uplink) signal and in the line below, the “response” (or downlink) signal.

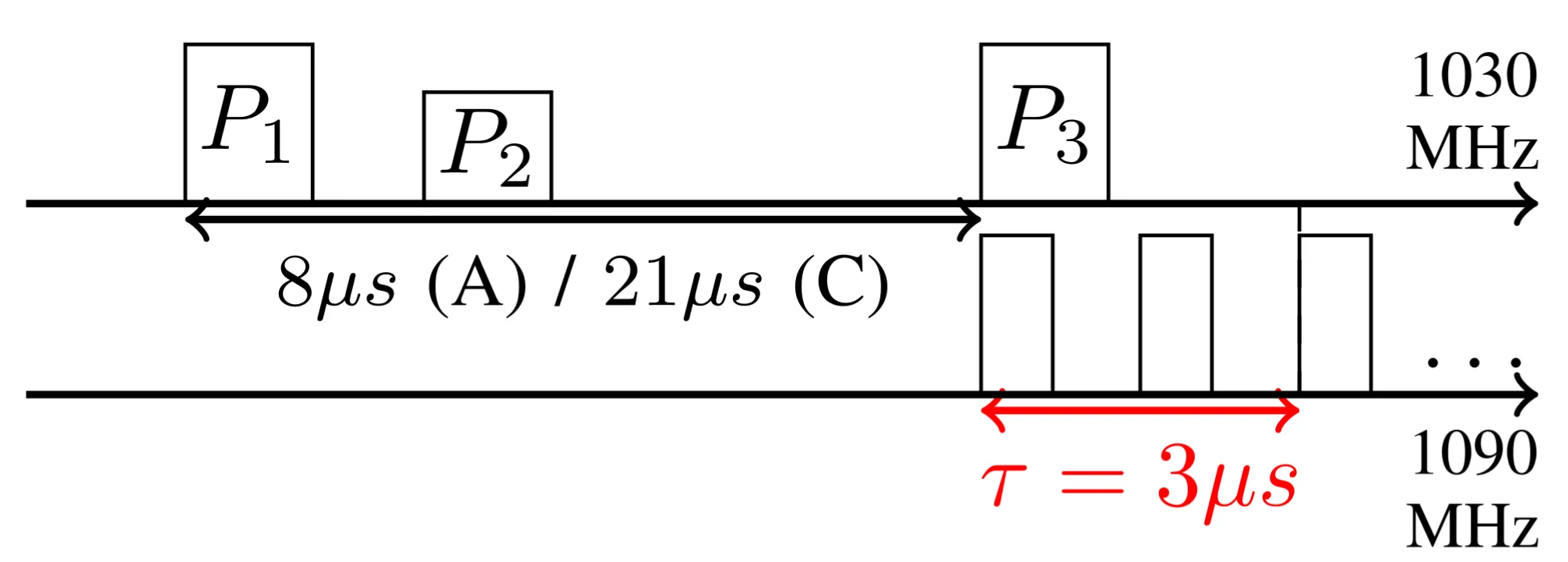

The attacker sits on the ground, far away. When they hear a query, they break the rule. They reply immediately, cutting out the processing wait time.

Because the reply arrives sooner than expected, the victim’s computer calculates that the source is much closer than the attacker actually is.

This is called “Range Spoofing”.

Immediate reply attack

In the image, this attack, in which the attacker replies without waiting and reduces the perceived range by around 0.9 km.

Mode discrimination attack

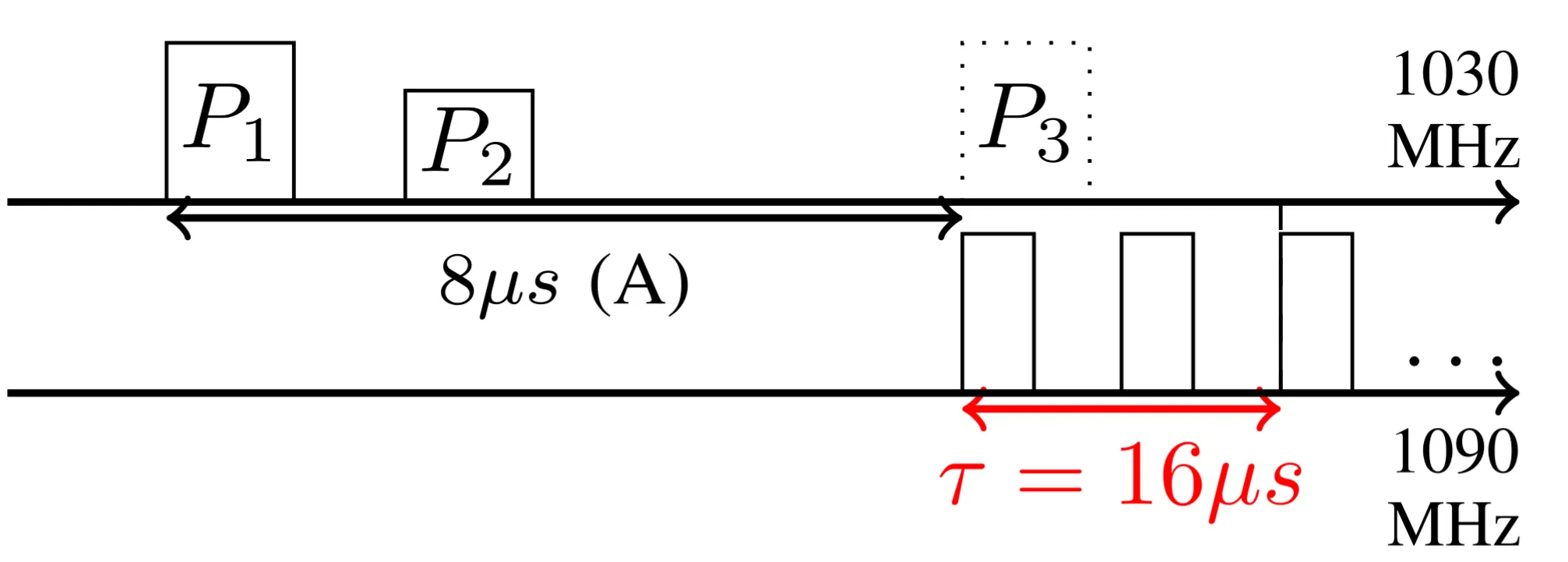

Looking at the first image a detail might have piqued your interest: the interrogation signal pulse P3 can be at either 8 or 21 microseconds after the interrogation pulse P2. This is because the distance in between P2 and P3 indicates to the receiver which information is being asked for. That can either be the identification code (Mode A, 8 microseconds) or the altitude (Mode C, 21 microseconds).

TCAS does not care about the Mode A code.

Exploiting this, the attacker can send its reply as soon as it hears the interrogation and is sure that it is not a Mode A interrogation. To do that, it can use the fact that the interrogation P3 is always at 8 microseconds after P2 in Mode A, so, if there is no P3 to be found, it can reply immediately after the would-be Mode A P3 pulse. This allows to compensate even more range, approximately 2.4 km.

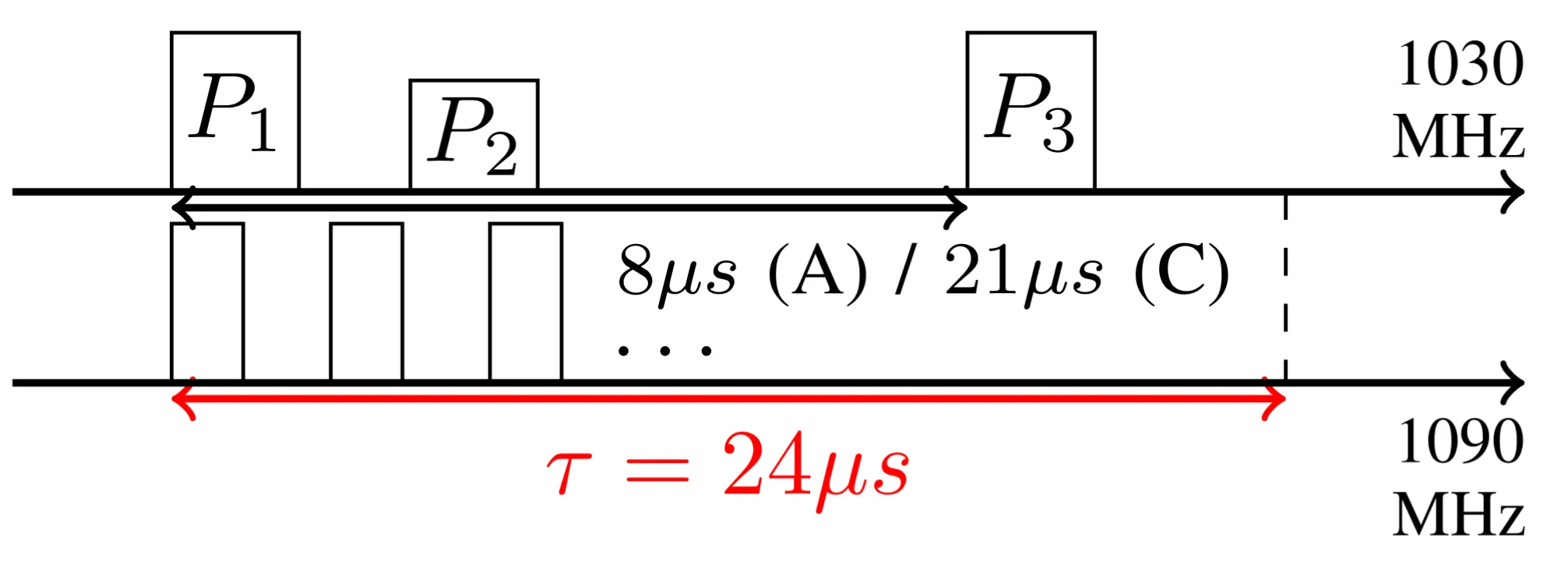

Preemptive reply attack

Finally, the most aggressive strategy is the “Preemptive Reply” attack, in which the attacker simply replies as soon as it hears P1. This allows to compensate even more range, approximately 3.5 km. But it may introduce errors in the interrogator as it may receive the reply before the interrogation is even over and make the attacker plane appear in two places at the same time.

Hunting the Signal: SMC-RAT

We cannot trust the ghost plane’s location. But we can trust physics.

We developed a method called SMC-RAT (Sequential Monte Carlo for Rogue ACAS Transmitters) to pinpoint the attacker.

It works like this:

1. Gathering Data

The attacker sends fake signals to multiple planes. Each plane records a different “ghost” location relative to itself. This location is defined in terms of bearing and range w.r.t. to the affected plane.

2. Particle Filters

Using Particle Filters (a statistical method belonging to the family of Sequential Monte Carlo methods), the system creates thousands of guesses about where the attacker might be. Each new encounter between the attacker and a victim updates these guesses, refining the system’s belief about the attacker’s location.

3. Convergence

As more planes fly by, impossible locations are filtered out. The map converges on a single area: the approximate location of the transmitter.

- The system starts with a large number of random guesses (particles).

- Each guess is updated based on the new information (the new encounter).

- The system then refines its belief about the attacker’s location by removing the guesses that are least likely to be correct. Those take into account data about the encounter: if the attacker is reported to be at a certain distance from the affected plane, the system will remove the guesses that are too far or too close.

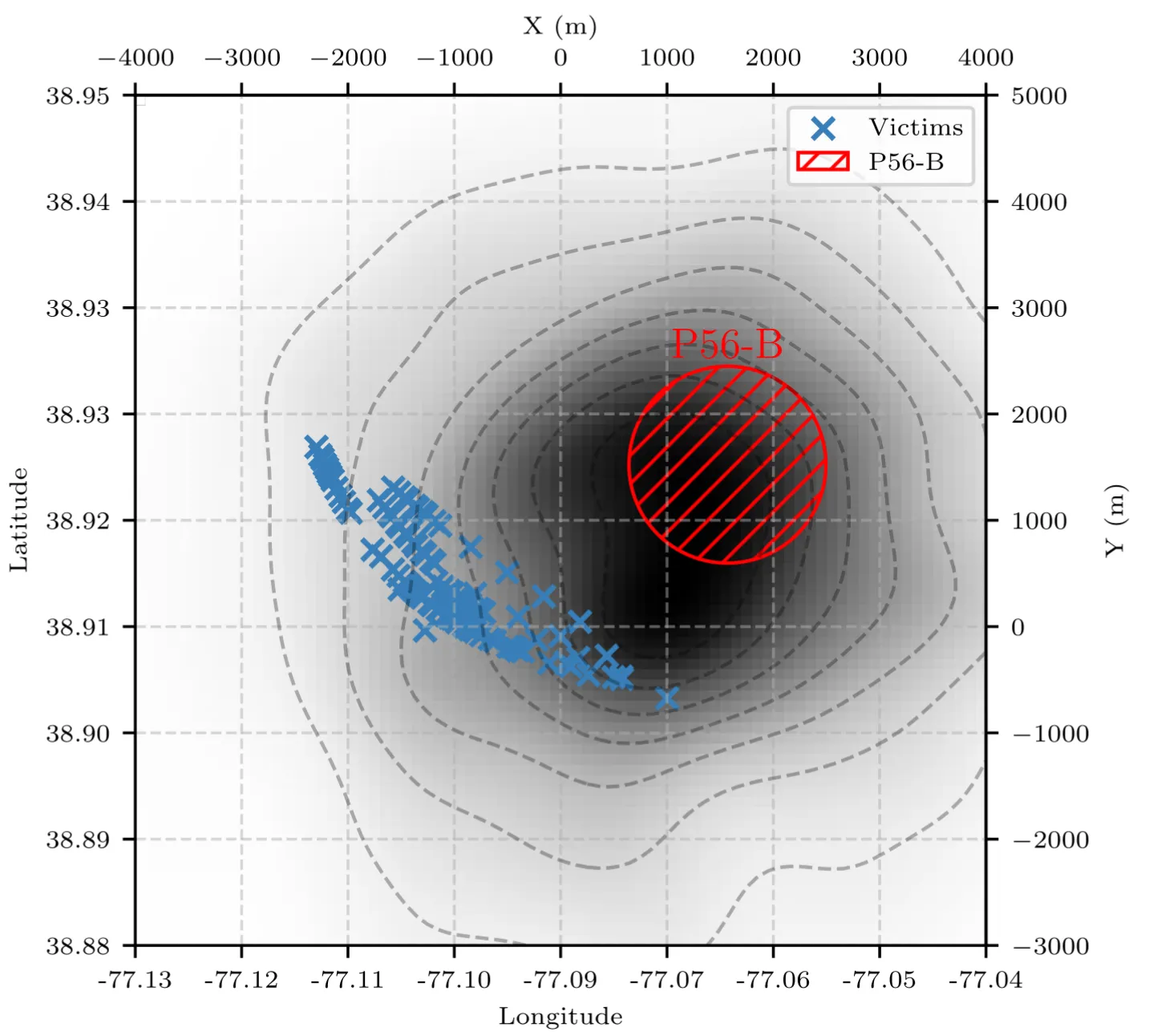

In the Washington incident, this method narrowed the search to a 4.3 km² area, identifying the likely source near a restricted zone (P-56B).

Demo: Try SMC-RAT

Experience how particle filters can localize a rogue transmitter.

Watch as planes fly through the area, each receiving spoofed signals from the hidden attacker. The green particles represent hypotheses about the attacker’s location, observe how they converge as more observations are collected.

SMC-RAT Simulation

Sequential Monte Carlo for Rogue ACAS Transmitters

What you’re seeing:

- Green dots: Each dot is a “particle”: a hypothesis about where the attacker might be

- Red X: The true (hidden) location of the rogue transmitter

- Blue triangles: Victim aircraft receiving spoofed TCAS signals

- Yellow circle: The estimated position based on all particles

Try adjusting the Range Spoofing (τ) slider to see how more aggressive attacks (higher values) make localization harder.

Footnotes

Metadata

Title Unknown Target: Uncovering and Detecting Novel In-Flight Attacks to Collision Avoidance (TCAS)

Authors Giacomo Longo, Giacomo Ratto, Alessio Merlo, Enrico Russo

Venue Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2026

Conference location San Francisco, CA, USA

Conference start date 2026-02-23

Conference end date 2026-02-27

DOI 10.14722/ndss.2026.241806

ISBN 979-8-9919276-8-0